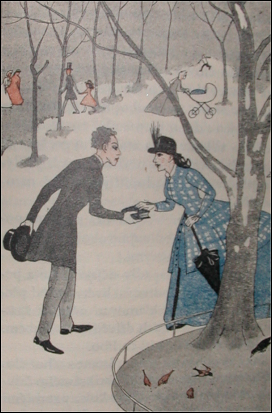

That is why next day Samuel took great care to bring her back her handkerchief and her book, which he found on a bench, and which she had not lost, since she was close at hand watching the sparrows squabbling for crumbs, or seeming to contemplate the inner workings of the vegetation. As often happens between two beings whose souls by a complicity of destiny have been brought into tune with one another, opening the conversation rather abruptly, he had, nevertheless, the good fortune to find a person disposed to listen and to reply to him.

‘Is it possible, madame, that I am fortunate enough to be still esconced in a corner of your memory? Have I changed so much that you cannot recognize in me a comrade of your childhood with whom you deigned to play at hide-and-seek, and to play truant?’

‘A woman’, replied the lady with a half smile, ‘has not the right to remember people so easily; that is why I thank you, sir, for being the first to afford me the opportunity of recalling those beautiful and joyous memories. And then—each year of life contains so many events and thoughts—and really it seems to me that it is many years ago?’

‘Years,’ replied Samuel, ‘which for me have been sometimes very slow, sometimes very quick to flee away, but all diversely cruel!’

‘And poetry?’ said the lady with a smile in her eyes.

‘Always, madame!’ replied Samuel laughing. ‘But what is that you are reading?’

‘A novel of Walter Scott’s.’

‘Now I understand your frequent interruptions. Oh, what a tiresome writer! A dusty unearther of chronicles! A wearisome pile of description and bric-a-brac, a heap of all sorts of old things and costumes: armour, crockery, furniture, Gothic inns and melodramatic castles, through which stalk a few puppets on strings, dressed in motley doublet and hose; hackneyed types which no eighteen-year-old plagiarist will look at in ten years; impossible ladies and lovers completely devoid of actuality, no truth of the heart, no philosophy of the sentiments! How different from our good French novelists, where passion and morality are always preferred to the material descriptions of objects! What does it matter whether the lady wears ruff or panniers or an Oudinot underskirt provided she sobs or betrays properly? Does the lover interest you much more because he carries a dagger in his waistcoat instead of a visiting card, and does a despot in a black coat terrify you less poetically than a tyrant encased in leather and mail?’

Samuel, as you see, was drifting into the category of intense people, intolerable and passionate men whose profession ruins their conversation, and for whom every occasion is a good one, even an acquaintanceship struck up under some tree or at some street corner—were it with a rag-picker—obstinately to develop their ideas. The only difference between commercial travellers, roving industrials, hopeful commission agents, and intense poets is the difference between advertising and preaching; the latter vice is quite disinterested.

Now, the lady answered him simply.

‘My dear Monsieur Samuel, I am merely the public, that is sufficient to tell you that I have an innocent soul. Consequently pleasure is for me the easiest thing in the world to find. But let’s talk of yourself: I should esteem myself fortunate were you to judge me worthy of reading some of your productions.’

‘But, madame, how does it happen — ?’ exclaimed the swollen vanity of the astonished poet.

‘The proprietor of my circulating library says that he does not know you!’

And she smiled sweetly as if to deaden the effect of this fleeting, teasing thrust.

‘Madame,’ said Samuel sententiously, ‘the true public of the nineteenth century is the women; your support will make me greater than twenty academies.’

‘Well, sir, I count on your promise. Mariette, the parasol and the scarf. Somebody is perhaps getting impatient at home. You know your master is coming back early.’

She made him a graceful, abrupt little bow, which was not in the slightest compromising, and the familiarity of which was not without a certain dignity.

Samuel was in no wise astonished to discover a former youthful love chained by the conjugal tie. In the universal history of sentiment, that is in order. She was called Madame de Cosmelly and lived in one of the most aristocratic streets in the Faubourg Saint-Germain.

Next day he found her, head inclined, in a graceful, almost studied melancholy, towards the flowers in the border, and he offered her his volume of T

he Ospreys, a collection of sonnets such as we all have written, and all have read in the days when our judgment was so short and our hair so long.

Samuel was very curious to know whether his

Ospreys had charmed this beautiful melancholy soul, and whether the screams of these nasty birds had disposed her favourably towards him; but a few days later she said to him with despairing candour and honesty:

‘Sir, I am only a woman, and consequently my judgment is of little account; but it seems to me that the sorrows and loves of authors have very little resemblance to the sorrows and loves of other men. You address gallantries, excellent no doubt and exquisitely chosen, to ladies whom I esteem sufficiently to believe that they must sometimes be frightened by them. You sing of the beauty of mothers in a style which is bound to deprive you of their daughters’ suffrage. You inform the world that you are madly in love with the foot or hand of Madame So-and-so, who, let us suppose for her honour, spends less time in reading you than in knitting stockings and mittens for the feet and hands of her children. By a most peculiar contrast, the mysterious cause of which is still unknown to me, you reserve your most mystic incense for queer creatures who read still less than ladies, and you go into Platonic ecstasies before low-born sultanas who, it seems to me, at the sight of the delicate person of a poet must open eyes as big as those of cattle awakening in a conflagration. Again, I do not know why you are so fond of funereal subjects, and anatomical descriptions. When one is young, and when, like you, one possesses fine talent and all the presumed conditions of happiness, it seems to me much more natural to celebrate health and the joys of decent men than to practise anathemas and talking with

Ospreys.’

This was his reply to her:

‘Madame, pity me, or rather pity us, for I have many brothers of my kind; it is hatred of all the world and of ourselves which led us to those lies. It is from despair at not being noble and beautiful according to natural means, that we have so strangely painted our faces. We were so busy sophisticating our hearts, we have so much abused the microscope to study the hideous excrescences and the shameful warts with which they are covered, growths we arbitrarily magnify, that it is impossible for us to speak the language of other men. They live for the sake of living, and we, alas! we live for the sake of knowledge. There lies the whole mystery. Age changes but the voice, destroying only the teeth and hair: we have altered the accent of nature, one by one, we have eradicated the virginal purities with which our innate decency bristled. We psychologized like madmen who increase their mania by striving to understand it. The years merely distort the limbs, and we have deformed the passions. Woe, thrice woe to the weakly sires who made us rickety and abnormal, predestined as we are to give birth only to still-born offspring!’

‘More

Ospreys!’ said she. ‘Come, give me your arm and let us admire the poor flowers the spring has made so happy!’

Instead of admiring the flowers, Samuel Cramer, whose phase and period had arrived, began to turn into prose and to declaim a few bad stanzas composed in his first manner. The lady let him run on.

‘What a difference there is, and how little is left of the same man, save the memory! But memory is only a fresh suffering. What a beautiful time was that when morning never found us with knees stiff and racked by the fatigue of dreams, when our bright eyes laughed at all nature; when our sighs flowed gently without noise or pride! How many times in the leisure of imagination I have seen again one of those beautiful autumnal evenings when young souls make progress comparable to those trees which shoot up several handbreadths in a thunderstorm. Then I see, I feel, I understand! The moon awakens the big moths; the warm wind opens the petals of the belles-de-nuit; the water sleeps in the great fountains. Listen in spirit to the sudden valses of that mysterious piano. The perfumes of the storm come in at the windows; it is the hour when the gardens are full of pink and white dresses that do not fear the rain. The complaisant bushes catch at the fleeting skirts; dark hair and blond curls mingle in a whirling dance. Do you remember, madame, the enormous haystacks, so swift for sliding down, the old nurse so slow to pursue you, and the bell so prompt to call you back to your aunt’s watchful eye, in the great dining- room?’

Madame de Cosmelly interrupted Samuel by a sigh, made as if to open her lips, no doubt to beg him to stop, but he had already resumed.