A rather comic detail of this story, a sort of intermezzo to the painful drama which was about to be played between these four characters, was the misunderstanding about Samuel’s sonnets; for in the matter of sonnets he was incorrigible; one for Madame de Cosmelly, in which he praised, in mystic style, her Beatrice- like beauty, her voice, the angelic purity of her eyes, the chastity of her gait, etc., the other for Fanfarlo, in which he served her up a ragout of gallantries with enough seasoning to sting the most experienced palate, a type of poetry, by the way, in which he was a past master, and in which he had long ago outstripped the most Andalusian of Andalusians. The first morsel went to the creature, who threw this dish of cucumber into her cigar-box; the second to the poor deserted one, who first stared, then finally understood, and, despite her grief, could not help bursting out laughing as in better days.

Samuel went to the theatre and began to study Fanfarlo on the boards. He found her light, magnificent, vigorous, full of taste in her accoutrements, and considered M. de Cosmelly very lucky to be able to ruin himself for such a piece.

He presented himself twice at her house, a villa with velvety staircase, full of portieres and carpets, in a new and leafy district, but under no reasonable pretext could he gain admission. A declaration of love was a profoundly useless and dangerous thing. One rebuff would have prevented him from returning. As for getting himself introduced, he learnt that Fanfarlo never received. A few close friends saw her from time to time. What could he say or do in the house of a dancer magnificently salaried and maintained, and adored by her lover? What could he bring her, he who was neither tailor nor dressmaker, ballet master, or millionaire? He therefore took a brutal and simple decision: Fanfarlo must come to him. At this period, critical and eulogistic articles had more value than now. The facilities of the feuilleton, as a worthy lawyer recently said in a sadly celebrated case, were much greater than to-day; a few talented artists having sometimes capitulated to the journalists, the influence of these adventurous and hair- brained youths no longer knew any bounds. So Samuel undertook—he who did not know a word of music—the special work of criticizing lyrical plays.

Henceforth Fanfarlo was weekly and savagely slated in the bottom columns of an important paper. It was impossible to say, or even hint that her legs, ankles, or knees were badly shaped; the muscles played beneath the stocking, and every opera-glass would have cried blasphemy. She was accused of of being brutal, common, devoid of taste, of wanting to import to our stage habits from beyond the Rhine or the Pyrenees, castanets, spurs, high heels, not to mention the fact that she drank like a trooper, was too fond of little dogs and her caretaker’s daughter, and other dirty linen of private life which is the daily meat and relish of

certain little newspapers. With those tactics peculiar to journalists, who insist on comparing dissimilar things, he held up against her an ethereal dancer, always dressed in white, whose chaste movements left every conscience at rest. Sometimes, Fanfarlo shouted and laughed very loudly to the pit when she finished a bound at the footlights; she dared to walk while dancing. Never did she wear those insipid gauzy dresses which show everything and leave nothing to the imagination. She loved stuffs that made a noise, long, crackling, spangled, tinselled dresses, which have to be lifted very high with a vigorous knee, the kind of corsages worn by mountebanks; she danced not with curls, but with ear-rings, I might say candelabras. She would have liked to have tied a crowd of little dolls to the bottom of her skirts, like those old gipsies who tell your fortune with a threatening air, and who are to be met at high noon under the arcades of Roman ruins; drolleries all of which the romantic Samuel, one of the last romantics possessed by France, very much adored.

So much so, that having run down Fanfarlo for three months, he fell madly in love with her, and she finally wanted to know who was the monster, the heart of bronze, the pedant, the half-wit who so obstinately denied the royalty of her genius.

This much justice must be accorded to Fanfarlo; all that actuated her was idle curiosity, nothing more. Had such a man really a nose in the middle of his face, and was he shaped quite like his fellow-beings? When, after having made one or two inquiries about Samuel, and learnt that he was a man like any other, of some sense and some talent, she understood vaguely that there was some mystery, and that this terrible Monday article might very well be only a peculiar sort of weekly bouquet, or the visiting card of an obstinate suitor.

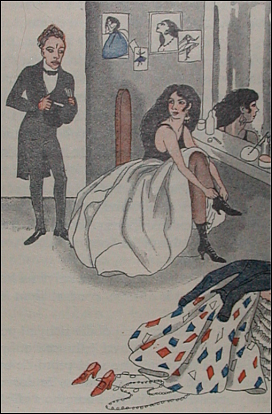

He found her one evening in her box. Two great candles and a big fire made their lights flicker on the motley costumes which littered this boudoir.

The queen of the place, about to leave the theatre, was reassuming the garb of an ordinary mortal and, crouched in a chair, was putting on her shoes, shamelessly revealing an adorable leg; her hands, plumply slender, made the lace of the buskin play through the eyelet holes like an agile shuttle, without a thought of the skirt which should have been pulled down. The leg was already for Samuel an object of eternal desire. Long, slender, strong, plump yet sinewy, it had all the correctness of the beautiful, and all the wanton allure of the pretty. Had it been dissected perpendicularly at its widest place, this leg would have offered a sort of triangle whose apex would have been situated on the tibia, and of which the rounded line of the calf would have furnished the convex base. A regular man’s leg is too hard, the women’s legs drawn by Devéria are too soft to give you an idea of it.

In this agreeable attitude, her head, bent towards her foot, displayed a proconsular neck, broad and strong, and allowed one to guess at the line of the shoulder-blades covered with brown abundant flesh. The thick, heavy hair fell forward on both sides, tickling her bosom and blinding her eyes, so that at every other moment she had to disturb and toss it back. A petulant, charming impatience, like that of a spoiled child who finds that things are not going fast enough, animated the whole creature and her clothing, and at every instant disclosed new points of view, new effects of line and colour.

Samuel stopped respectfully, or pretended to stop respectfully; for with this confounded fellow the great problem is always to know where the actor begins.

‘Ah! there you are, monsieur!’ she said to him without disturbing herself, though she had been told a few minutes previously about Samuel’s visit.

‘You’ve something to ask me, haven’t you?’

The sublime impudence of these words went straight to poor Samuel’s heart; he had chattered like a romantic magpie for a whole week at Madame de Cosmelly’s; here he quietly replied:

‘Yes, madame!’

And tears came to his eyes.

That had an enormous success. Fanfarlo smiled.

‘And what insect has been stinging you, monsieur, that you bite at me so savagely? What a frightful profession — ’

‘Frightful indeed, madame. The fact is, I adore you.’

‘I thought as much,’ replied Fanfarlo. ‘But you are a monster. These are abominable tactics. Poor girls that we are!’ she added laughing. ‘Flore, my bracelet. Give me your arm to my carriage, and tell me whether you liked me this evening.’

They went off thus, arm in arm, like two old friends. Samuel was in love, or at least felt his heart beating hard. He was perhaps odd, but certainly, this time he was not ridiculous.

In his joy, he had almost forgotten to warn Madame de Cosmelly of his success, and to bring hope to her deserted home.

A few days afterwards, Fanfarlo was playing the part of Columbine in a huge pantomime created for her by some men of genius. Here, by an agreeable succession of transformations, she appeared in the characters of Columbine, Marguerite, Elvire and Zépherine, and, in the gayest possible way, received the kisses of several generations of personages borrowed from various countries and various literatures. A great musician had not disdained to write a fantastic score appropriate to the queerness of the subject. Fanfarlo was, in turn, respectable, fairy-like, mad, mirthful; she was sublime in her art, as much an actress with her legs as a dancer with her eyes.

In our country the art of dancing is too much despised, let me say in passing. All great nations, first of all those of the ancient world, those of India and Arabia have cultivated it to the same extent as poetry. Dancing is as much above music, for certain pagan temperaments at least, as the visible and created are above the invisible and uncreated: only those can understand me to whom music gives pictorial ideas. Dancing can reveal all the mystery hidden in music, and it has, moreover, the merit of being human and palpable. Dancing is poetry with arms and legs: it is matter, graceful and terrible, beautified by movement. Terpischore is a southern muse; I presume she was very dark, and often shook her feet in the golden wheat; her movements, full of precise cadence, are so many divine motifs for the sculptor. But Fanfarlo, the Catholic, not content with rivalling Terpischore, called to her aid all the art of more modern divinities. Commingled in the mists are forms of fairies and water-sprites less diaphanous and less nonchalant. She was at once a Shakespearean caprice and an Italian drollery.

The poet was delighted; he thought he saw before his eyes the dream of his earliest days. He would willingly have cut ridiculous capers in his box and bumped his head against something in the mad intoxication that possessed him.

A low, close-curtained carriage rapidly carried the poet and the dancer towards the villa of which I have spoken.

Our man expressed his admiration by silent kisses which he fervently showered on her hands and feet. She too admired him very much, not that she was ignorant of the power of her charms, but she had not met a man so odd or a passion so electric.