Samuel did not exactly see what this charming victim was driving at, but he began to find that she was talking too much about her husband for a disillusioned woman.

After a pause of a few moments as if she feared to approach the fatal spot, she resumed thus:

‘One day M. de Cosmelly wanted to return to Paris; it was necessary that I should shine in my own light and be in a setting worthy of my merit. A beautiful and clever woman, he said, owes herself to Paris. She must know how to pose before society, and shed some of her reflected light on her husband. A woman of noble mind and good sense knows that she has no glory to expect in the world save in so far as she shares the glory of her travelling companion, serves the virtues of her husband, and above all, that she obtains respect only in so far as she makes him respected. Of course, it was the simplest, surest way of getting himself obeyed almost joyously. To know that my efforts and my obedience would make me more beautiful in his eyes: it did not require even as much as that to decide me to face this terrible Paris, of which I was instinctively afraid, and the black, dazzling ghost of which, looming on the horizon of my dreams, sent a shudder through my poor girlish heart. That then, according to him, was the real reason for our journey. A husband’s vanity constitutes the virtue of a loving wife. Perhaps he was lying to himself in a sort of well-meaning way, and cheating his conscience without being aware of it.

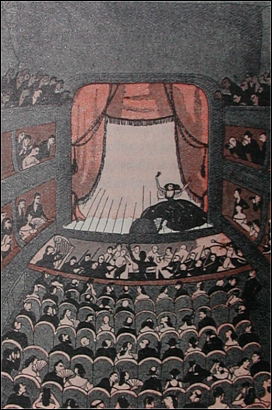

In Paris we had days reserved for close friends of whom, in the long run, M. de Cosmelly got bored as he had got bored with his wife. Perhaps he had got a little disgusted with her because she was too loving; she kept none of her love back. He got disgusted with his friends for the opposite reason. They had nothing to offer him save the monotonous pleasures of conversations where passion has no share. Henceforth, his activity took another direction. After his friends came horses and cards. The hum and stir of society, the sight of those who had remained unfettered, and who gave endless accounts of the memories of a mad, busy youth, snatched him from his fireside and our long intimate talks. He who had never had any business but his heart, became a busy man. Rich and without profession, he managed to create a crowd of bustling, frivolous occupations which filled all his time. “Where are you going?” “At what time shall I see you again?” “Come back quickly” — these wifely questions I had to thrust back again down into the depths of my heart: for English life — that death of love — the life of clubs and meetings absorbed him completely. The exclusive care he took of his person, and the dandyism he affected, shocked me to begin with; obviously I was not the object of it. I tried to be like him, to be more than beautiful, that is to say to be coquettish, attractive for him as he was for everybody; where formerly I used to offer everything and give everything, now I wanted to be pleaded with. I wanted to rekindle the ashes of my dead happiness by shaking and stirring them; but apparently I am not very clever at deception, and very awkward at vice. He did not even condescend to notice it. My aunt, cruel like all old and envious women, who are reduced to admiring a show in which they were formerly actresses, took great care to let me know, through the interested medium of a cousin of M. de Cosmelly’s, that he had fallen in love with an actress who was then the rage. I made them take me to all the plays, and, at the appearance on the stage of every good-looking woman I trembled lest I was admiring my rival. Finally, by the charity of the same cousin, I learned that it was Fanfarlo, an actress as stupid as she was beautiful. You who are an author, you know her of course. I am not very vain or proud of my looks, but I swear to you, M. Cramer, that many a time at night, about three or four in the morning, tired of waiting for my husband, my eyes red with tears and lack of sleep, after long and beseeching prayers for his return to fidelity and duty, I asked God, my conscience, and my mirror, if I was as beautiful as that wretched Fanfarlo. My mirror and my conscience replied “Yes”. God forbade me to be proud of it, but did not forbid me to derive a legitimate victory from the fact. Why, then, between two equal beauties, do men often prefer the flower whose perfume every one has inhaled to that which had always kept aloof from passers-by in the darkest walks of the conjugal garden? Why is it, then, that women who are prodigal with their bodies, a treasure of which only one sultan should have the key, possess more adorers than we others, unfortunate martyrs of a solitary love? What is the magic charm which vice sets like a halo on the brow of certain creatures? What awkward and repulsive aspect does virtue lend to certain others? Tell me, you who from your profession must know all the sentiments of life and their various reasons.’

Samuel had no time to reply, for she continued ardently:

‘M. de Cosmelly has very grave things on his conscience if the loss of a young and virginal soul interests the God who created it for the happiness of another. If M. de Cosmelly were to die this very evening he would have a great many pardons to implore; for, by his fault, he has taught his wife dreadful sentiments, suspicion of a loved one, and the thirst for revenge. Ah, monsieur, I spend nights of great sorrow and sleepless anxiety: I pray, I curse, I blaspheme. The priest tells me I must bear my cross with resignation, but you cannot teach resignation to insane love and shattered faith. My confessor is not a woman, and I love my husband; I love him with all the passion and all the grief of a mistress beaten and trodden under foot. There is nothing I have not tried. Instead of the dark and simple dresses that formerly pleased his eye, I have worn dresses as crazy and sumptuous as those of actresses. I, the chaste wife whom he had discovered hidden in an old château, I paraded before him dressed like a courtesan. I made myself witty and gay when death was in my heart. I spangled my despair with glittering smiles. I put on rouge, sir, I put on rouge! You see it is a banal story, the story of all unhappy women, a provincial novel!’

Whilst she was sobbing, Samuel looked like Tartuffe in the grasp of Orgon, the unexpected husband who springs from his hiding place, as the virtuous sobs of the lady sprang from her heart, seizing our poet’s tottering hypocrisy by the scruff of the neck.

Madame de Cosmelly’s extreme self-abandonment, her freedom and confidence had prodigiously emboldened, without astonishing him. Samuel Cramer, who has often astonished the world, scarcely ever was astonished. In his life he seemed to try to practise and demonstrate the truth of that thought of Diderot’s: ‘Incredulity is sometimes the vice of a fool, and credulity the defect of a man of wit. The man of wit sees far into the immensity of the possible. The fool scarcely ever conceives as possible anything save what actually is. It is that perhaps which makes the one timid and the other bold’. This is the reply to everything. No doubt some scrupulous readers, who love probable truth, will find many objections to this story, in which, however, all I have had to do was to change the names and accentuate certain details; how is it, they will say, that Samuel Cramer, a poet of doubtful tone and morals, can so quickly approach a woman like Madame de Cosmelly? And how can he, apropos of a Scott novel, flood her with a torrent of romantic and banal poetry? How can Madame de Cosmelly, the discreet and virtuous spouse, pour out to him, without shame or mistrust, the secret of her sorrows? To which I reply that Madame de Cosmelly was a simple, beautiful soul, and that Samuel was bold like all butterflies, cockchafers and poets: he threw himself into all sorts of flames and entered all sorts of windows. Diderot’s thought explains why one was so abandoned, and the other so brusque and so shameless. It explains, too, all the blunders Samuel committed in his life, blunders which a fool would not have committed. That portion of the public which is essentially pusillanimous will hardly understand the character of Samuel, who was essentially credulous and imaginative, to the point of believing—as a poet, in his public—as a man, in his own passions.

Now he perceived that this woman was stronger, more precipitous than she seemed, and that he must not dash, bull-headed, at this candid piety. Once more he served up his romantic jargon. Ashamed at having been stupid, he tried to be a roué; for a time he still spoke to her in a jesuitical strain of wounds to be closed or cauterized by opening fresh wounds which would bleed freely and painlessly. Anybody who, without possessing the absolutory power of Valmont or Lovelace, has desired to possess a decent woman who was not very interested, knows with what ridiculous and emphatic awkwardness every one says, showing his heart: ‘Take my bear’. This will dispense me from explaining to you how stupid Samuel was. Madame de Cosmelly, that amiable Elmire, who had the clear and prudent vision of virtue, saw promptly what advantage she could gain from this novice of a scoundrel, for her own happiness and for her husband’s honour. She therefore paid him in the same coin; she let him squeeze her hand; she spoke of friendship and Platonic matters. She murmured the word, vengeance; she said that in these painful crises of a woman’s life, one would willingly give to the avenger whatever was left of a heart abandoned by perfidy, and other dramatic sillinesses and marivaudage. In short, she played the coquette for a worthy purpose, and our young roué, who was simpler than a savant, promised to snatch Fanfarlo from M. de Cosmelly and rid him of the courtesan, hoping to find in the arms of the decent woman the reward of this meritorious work. It is only poets who are naive enough to invent monstrosities of this sort.